The story

A reader who would like to remain anonymous writes:

A story of research fraud just broke that I’d like to bring your attention to, if you haven’t heard it already.

Last year, a first year phd student in economics named Aidan Toner-Rodgers gained headlines for his paper on AI boosting scientific discovery. Acemoglu calls the work “fantastic” and David Autor was “floored.” I’m sure Autor was floored again when it was discovered that the entire thing was fake.

Hey, that’s a funny line!

My correspondent continues:

It seems TR made up everything; there likely was never an experiment in the first place. He even registered a domain name to look like Corning, who then sent him a cease-and-desist. This blog post by a material scientist points out some of the obvious red flags, as does this twitter thread by a professor of materials chemistry. MIT sent out a press release. They’ve asked arxiv to take down the paper and TR is no longer a student at MIT.

It’s an incredible story, especially given how popular that paper was upon the release of the preprint. It received an R&R from QJE and slipped by Acemoglu and Autor. I’ve been happy to see that the story of the fraud seems to be receiving about as much attention as the paper itself did upon release, but still sad that this could happen in the first place.

Hopefully my next correspondence with you is about research and not whatever this is.

“Whatever this is,” indeed!

I was curious so I googled the usual suspects (*Aidan Toner-Rodgers gladwell*, *Aidan Toner-Rodgers freakonomics*, *Aidan Toner-Rodgers NPR*, etc.), and some fun things came up:

From a Freakonomics episode, Is San Francisco a Failed State? (And Other Questions You Shouldn’t Ask the Mayor):

There was just a study from a grad student at M.I.T. describing how researchers using A.I. were able to discover 44 percent more materials than a randomly assigned group that didn’t have access to the technology.

From NPR’s Planet Money:

One of the big questions in economics right now is which types of workers benefit from the use of AI and which ones don’t. As we’ve covered before in the Planet Money newsletter, some early studies on Generative AI have found that less skilled, lower-performing workers have benefited more than higher skilled, higher-performing workers.

For economists like MIT’s David Autor, these early studies have been exciting. . . . Another recent study by MIT economist Aidan Toner-Rodgers found something similar. It looked at what happened to the productivity of over a thousand scientists at an R&D lab of a large company after they got access to AI. Toner-Rodgers found that “while the bottom third of scientists see little benefit, the output of top researchers nearly doubles.” Again, AI benefits those who can figure out how to use it well, and, it suggests, that in many fields, top performers could become more top performing, thereby increasing inequality.

Tyler Cowen shared the abstract of the Toner-Rodgers papers and none of his commenters sniffed out the problems.

Given that the paper fooled the reporters at the Wall Street Journal and the commenters at Marginal Revolution, it shouldn’t be such a surprise that perennially-credulous outlets such as Freakonomics and NPR fell for it too.

A smooth-looking research article . . .

After doing that quick web search, I followed the second link above to read Toner-Rodgers’s article. It was very well-written: it reads like a real econ paper! No wonder Acemoglu and Autor got conned: the paper is smooth and professional in appearance, down to the footnote on the first page thanking 21 different people as well as “seminar participants at NBER Labor Studies and MIT Applied Micro Lunch for helpful comments.” I’m reminded of the Technical Note at the end of the zombies paper.

. . . with some weird references

The first thing that jumped out at me was this in the reference list:

Diamandis, Peter. 2020. “Materials Science: The Unsung Hero.”

That guy’s a notorious bullshitter–how did that reference get into an otherwise serious-looking paper?

Actually, a lot of the references in Toner-Rodgers’s paper are incomplete, with no publication information at all, just a pile of things pulled off the internet, for example:

Bostock, J. 2022. “A Confused Chemist’s Review of AlphaFold 2.”

Cotra, Ajeya. 2023. “Language models surprised us.”

Ramani, Arjun, and Zhengdong Wang. 2023. “Why Transformative Artificial Intelligence is Really, Really Hard to Achieve.” The Gradient.

Schulman, Carl. 2023. “Intelligence Explosion.”

In the words of the late Joe Biden, “C’mon, man.”

The paper also cites 6 articles by Acemoglu and 6 by Autor . . . ok, I guess that’s why they were “floored” and thought the work was “fantastic.” If only Toner-Rodgers had found his way to including 10 references for each of them, maybe he could’ve moved up to “bowled over” and “amazing.”

Seriously, though, setting aside the junk references, I don’t know that I would’ve noticed any problems with the paper had it been sent to me cold.

Suspiciously wide confidence intervals

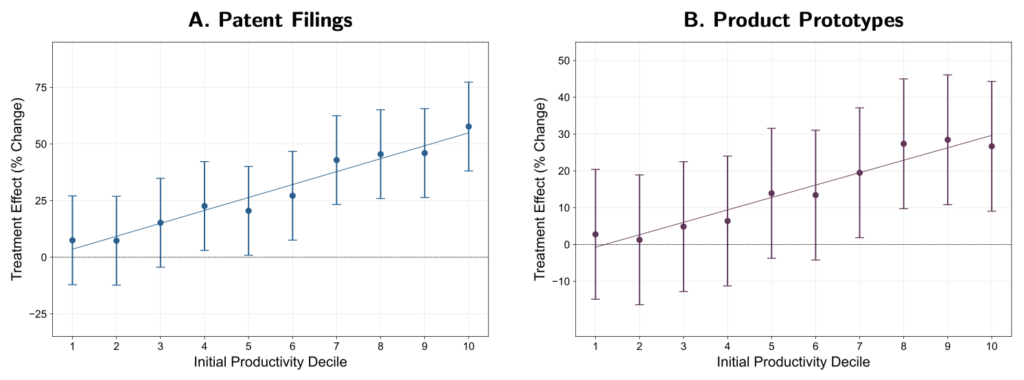

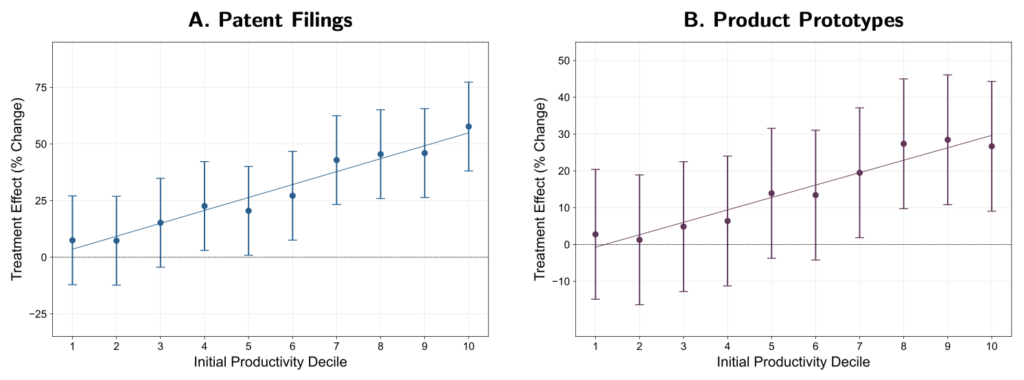

The only obviously suspect bits are Figures A.2 and A.3:

The intervals look too wide given how close the points are to the line. But my reaction in seeing something like this is that the model is probably misspecified in some way, or maybe the authors are reporting the results wrong. These graphs don’t scream “Fraud!”; they scream, “Someone is using statistical methods beyond his competence” (as with the multilevel model discussed here).

Funny p-values

Oh, yeah, there’s also Table A1:

Something funny about that first column, no? The estimate is 0.195, the standard error is 0.105, and it’s listed as significant at the 1% level. But 0.195/0.105 = 1.86, which, under the usual calculation, has a p-value of more than 5%.

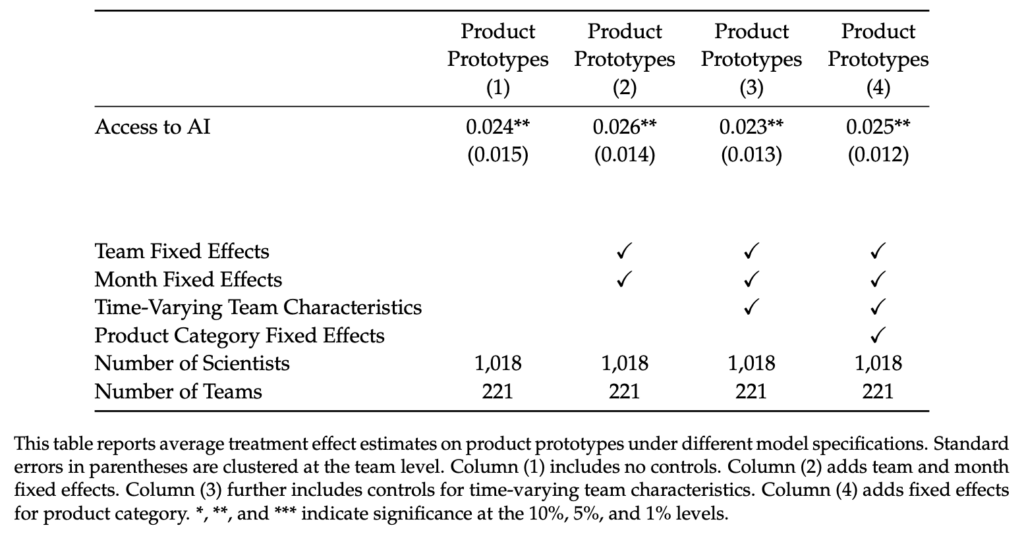

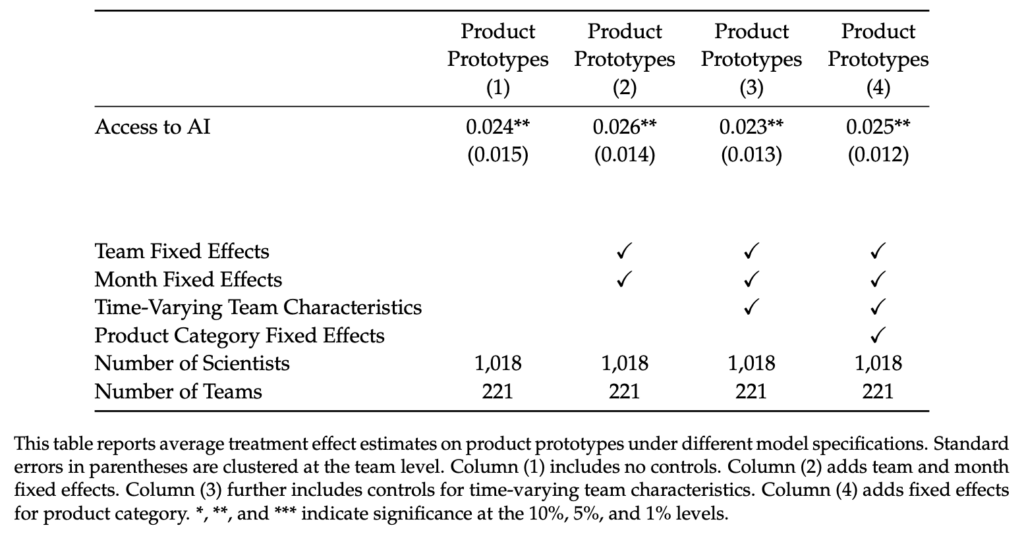

And Table A3:

0.024/0.015 = 1.6, but a z-score of 1.6 is not significant at the 5% level.

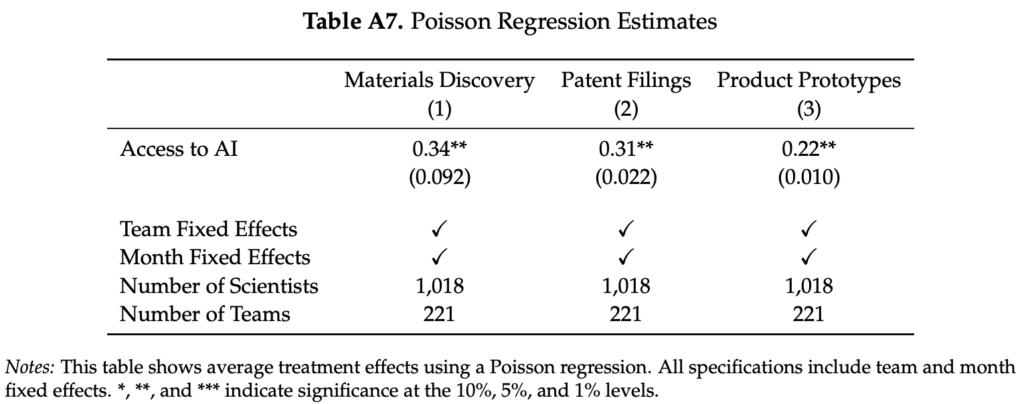

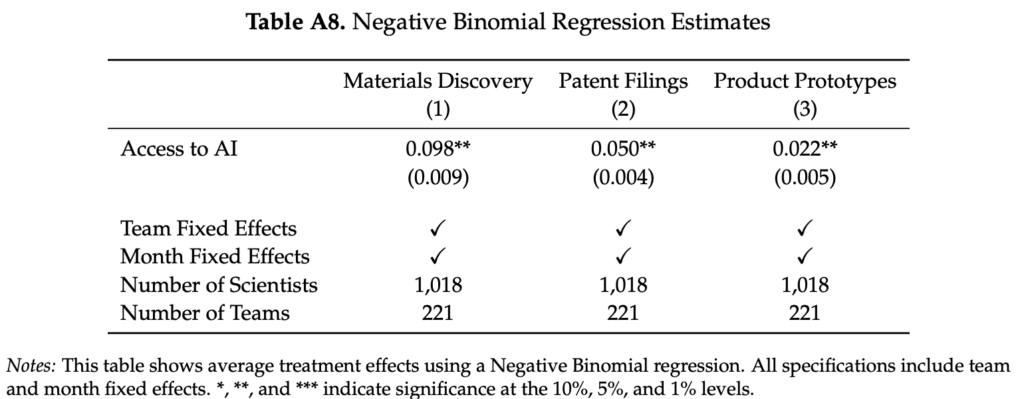

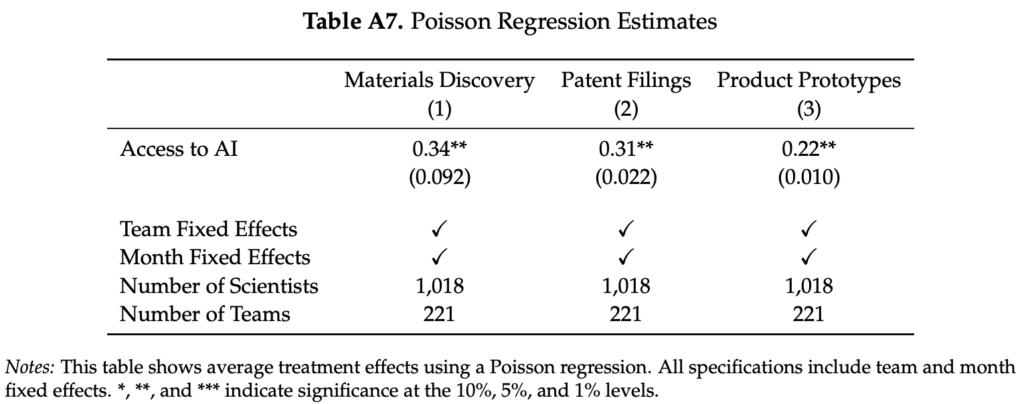

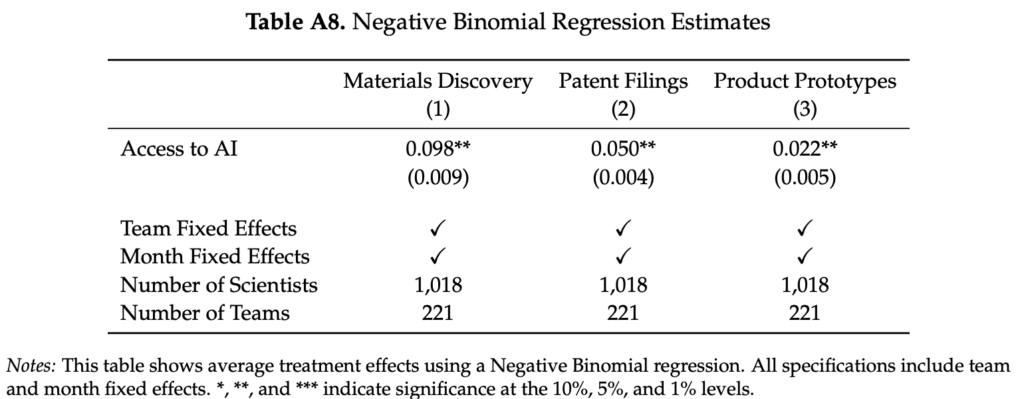

And then these:

First, this looks wrong because with Poisson and negative binomial regressions, you’ll typically get similar point estimates but a wider standard error for the negative binomial. But here the point estimates are much different, and something seems wrong with the standard errors: the negative binomial has tiny standard errors. And again the p-values don’t match the numbers in the table. The estimates in the first two columns of Table A8 are a stunning (one might say, suspicious) 10+ standard errors from zero, but they’re starred as not reaching the 1% level of significance.

It’s kind of amazing for someone to have put so much effort into (allegedly) faking an entire study and then get sloppy at that last bit. Maybe he should’ve faked all the raw data so as to ensure internal consistency of his results. I kinda wonder where all these numbers came from. Maybe he used a chatbot to produce them? It would be kind of exhausting to construct them all from scratch.

That all said, had I been a reviewer I might have pointed out these anomalies, and then the numbers could’ve been cleaned up in the revision process and I’d have been none the wiser.

How did they spot the fraud?

OK, so my next question is, who figured out the paper was a fake, and how did they figure it out? From the Wall Street Journal article:

[Acemoglu and Autor] said they were approached in January by a computer scientist with experience in materials science who questioned how the technology worked, and how a lab that he wasn’t aware of had experienced gains in innovation.

Credit to Acemoglu and Autor for accepting this and not trying to shoot the messenger. Also credit to MIT, which did better than Columbia, UCB, and USC in handling research misconduct. I guess it’s easier to discipline a misbehaving student than a misbehaving professor. In any case, as an MIT alum, I appreciate their statement, “Research integrity at MIT is paramount – it lies at the heart of what we do and is central to MIT’s mission.” In this case, they talk the talk and they walk the walk.

To learn more I followed the link above to the material scientist’s blog post, which gives lots of details on suspicious aspects of the paper, various things that I wouldn’t have noticed–no surprise, given that the last time I published anything in material science was over 40 years ago! I recommend you read the whole thing (the material science post, not my old physics paper).

A story worthy of Borges

Above I asked, how is is that this student reportedly went to the trouble to make up an entire study, complete with a fake webpage, and complete and submit a long, professionally-written research paper based on fake study, and then fall down on his p-value calculations. Converting a z-score to a p-value, that’s the easiest thing in the world, no?

But after reading the report by the material scientist, I’m not so sure, as the p-values appear to be the least of the issues. If anything, Toner-Rodgers should’ve put less effort into faking the statistical summaries and more work into designing a more convincing fake study.

But it’s hard to design a convincing fake study. Fake things look fake. Reality is overdetermined. Remember that Borges story with a map that is on a one-to-one scale with reality? Anything else would be unrealistic. Similarly, if you want to fake a study, it should be coherent, and the only way to do that is to not just fake the tables but to fake the raw data, but then outsiders can check the raw data and find evidence for its construction, so really to be on the safe side you need to actually gather the data, which means you need to perform the study.

In short, the only way to produce a truly convincing fake experiment is . . . to do the experiment for real. But that would take a lot of work! (Also there’s a risk with real data that you might not find the effect you’re looking for, but modern methods of data analysis have enough researcher degrees of freedom that this shouldn’t be a problem.)

So, yeah, Toner-Rodgers showed real talent in writing a real-looking paper with lots of almost-real-looking tables and graphs–but perhaps his most impressive achievement was in “social engineering”: whatever it took for him to persuade Acemoglu, Autor, and others that he’d done a real study. You gotta be a stone-cold faker to pull that off.

A solution that should make everyone happy

The above-linked news article said that the author of this apparently-fraudulent paper is no longer at MIT. But this shouldn’t be a problem. When authors of fraudulent papers leave MIT, they usually can go to Duke, no? There must be a position in the business school for this guy. He has a great future ahead of him. Maybe some Ted talks?

Failing that, I’ve heard that UNR is doing a search for dean of engineering. “Artificial Intelligence, Scientific Discovery, and Product Innovation” sounds perfect for that, no? But really I think that Duke’s Fuqua School would be ideal, a place where he could be mentored by one of their senior faculty with very relevant expertise.